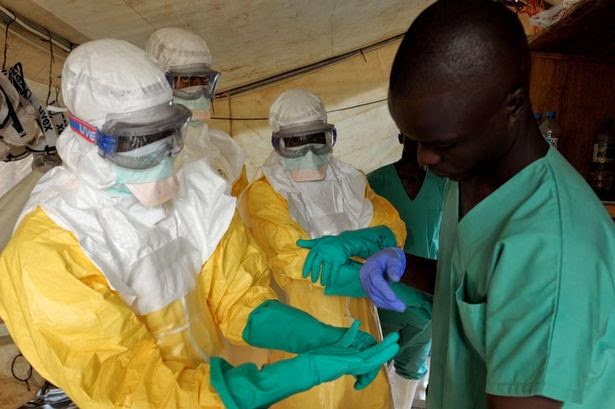

Protection: Health specialists work in an isolation ward in southern Guinea

Conspiracy theories about Ebola are spreading as fast as the killer virus itself.

And with no known cure or vaccine, its potential origins vary wildly from it being a CIA-manufactured weapon to a cover for "cannibalistic rituals."

Angry crowds in Africa have also accused foreigners of bringing the virus into the country.

In April, the threat of violence forced Medecins Sans Frontieres to evacuate all its staff from a treatment centre in Guinea.

In Sierra Leone, which has the largest number of Ebola cases, thousands protested outside the country's main Ebola treatment facility in the eastern city of Kenema, where police had to disperse the crowd with tear gas.

Reports say the demonstration was sparked by a rumour from a nearby market that the disease was a ruse used to justify "cannibalistic rituals" being carried out in the hospital.

Dr Leonard Horowitz, an international authority on public health education, has conducted a major study into the origin of AIDS and Ebola, questioning claims they are emerging viruses that jumped from ape to man.

In his book Emerging Viruses, he investigates the possibility the germs were laboratory creations, accidentally or intentionally transmitted via tainted hepatitis and smallpox vaccines.

He also examines CIA activities and foreign policy initiatives in Central Africa in response to alleged threats posed by communism, black nationalism, and Third World populations.

UNICEF says rumours and denial are fuelling the spread of Ebola in Africa and putting even more lives at risk.

Manuel Fontaine, UNICEF Regional Director for West and Central Africa says some people still deny that the disease is real. Others believe it doesn’t have to be treated.

Ebola Virus Graphic

Widespread misconception, resistance, denial and occasional hostility in some communities are considerably complicating the humanitarian response to contain the outbreak.

Fontaine said: "The response goes beyond medical care. If we are to break the chain of Ebola transmission, it is crucial to combat the fear surrounding it and earn the trust of communities.

"We have to knock on every door, visit every market and spread the word in every church and every mosque. To do so, we urgently need more people, more funds, more partners.”

The World Health Organisation has taken some bizarre inquiries from worried Africans: Will eating raw onions once a day for three days protect me from Ebola? Is it safe to eat mangoes? Is it true that a daily intake of condensed milk can prevent infection with Ebola?

Protection: Doctors Without Borders wear protective gear in Conakry

These are just some of the questions posed to health workers responding round the clock to calls received through the free Ebola hotline in Guinea.

“Some people who call are in panic and false rumours make it difficult to calm them down”, says Dr Saran Tata Camara, one of the doctors who takes the calls.

“But if we tell them that it is not easy to contract Ebola and that they can protect themselves if they respect some rules, they often understand.”

In 2000, Uganda suffered an outbreak that ultimately killed 224 people — yet patients often ran away from ambulances and hid when health workers came looking for them.

Tragic: Health workers carry the body of an Ebola virus victim in Kenema, Sierra Leone

And in 2003, according to the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, there were widespread fears that “Euro-Americans” were buying and selling body parts.

This paranoia was fuelled further by health workers’ practice of burying the bodies of Ebola victims as soon as possible.

But that meant many family members never saw their loved ones’ bodies. In Guinea, officials are working to ensure burial practices are not only medically safe but respectful of the local culture.

It is widely thought Ebola is first acquired by a population when a person comes into contact with the blood or bodily fluids of an infected animal like a monkey or fruit bat.

Fruit bats are believed to carry and spread the disease without being affected by it. Once infection occurs, the disease may be spread from one person to another.

SOURCE

Conspiracy theories about Ebola are spreading as fast as the killer virus itself.

And with no known cure or vaccine, its potential origins vary wildly from it being a CIA-manufactured weapon to a cover for "cannibalistic rituals."

Angry crowds in Africa have also accused foreigners of bringing the virus into the country.

In April, the threat of violence forced Medecins Sans Frontieres to evacuate all its staff from a treatment centre in Guinea.

In Sierra Leone, which has the largest number of Ebola cases, thousands protested outside the country's main Ebola treatment facility in the eastern city of Kenema, where police had to disperse the crowd with tear gas.

Reports say the demonstration was sparked by a rumour from a nearby market that the disease was a ruse used to justify "cannibalistic rituals" being carried out in the hospital.

Dr Leonard Horowitz, an international authority on public health education, has conducted a major study into the origin of AIDS and Ebola, questioning claims they are emerging viruses that jumped from ape to man.

In his book Emerging Viruses, he investigates the possibility the germs were laboratory creations, accidentally or intentionally transmitted via tainted hepatitis and smallpox vaccines.

He also examines CIA activities and foreign policy initiatives in Central Africa in response to alleged threats posed by communism, black nationalism, and Third World populations.

UNICEF says rumours and denial are fuelling the spread of Ebola in Africa and putting even more lives at risk.

Manuel Fontaine, UNICEF Regional Director for West and Central Africa says some people still deny that the disease is real. Others believe it doesn’t have to be treated.

Ebola Virus Graphic

Widespread misconception, resistance, denial and occasional hostility in some communities are considerably complicating the humanitarian response to contain the outbreak.

Fontaine said: "The response goes beyond medical care. If we are to break the chain of Ebola transmission, it is crucial to combat the fear surrounding it and earn the trust of communities.

"We have to knock on every door, visit every market and spread the word in every church and every mosque. To do so, we urgently need more people, more funds, more partners.”

The World Health Organisation has taken some bizarre inquiries from worried Africans: Will eating raw onions once a day for three days protect me from Ebola? Is it safe to eat mangoes? Is it true that a daily intake of condensed milk can prevent infection with Ebola?

Protection: Doctors Without Borders wear protective gear in Conakry

These are just some of the questions posed to health workers responding round the clock to calls received through the free Ebola hotline in Guinea.

“Some people who call are in panic and false rumours make it difficult to calm them down”, says Dr Saran Tata Camara, one of the doctors who takes the calls.

“But if we tell them that it is not easy to contract Ebola and that they can protect themselves if they respect some rules, they often understand.”

In 2000, Uganda suffered an outbreak that ultimately killed 224 people — yet patients often ran away from ambulances and hid when health workers came looking for them.

Tragic: Health workers carry the body of an Ebola virus victim in Kenema, Sierra Leone

And in 2003, according to the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, there were widespread fears that “Euro-Americans” were buying and selling body parts.

This paranoia was fuelled further by health workers’ practice of burying the bodies of Ebola victims as soon as possible.

But that meant many family members never saw their loved ones’ bodies. In Guinea, officials are working to ensure burial practices are not only medically safe but respectful of the local culture.

It is widely thought Ebola is first acquired by a population when a person comes into contact with the blood or bodily fluids of an infected animal like a monkey or fruit bat.

Fruit bats are believed to carry and spread the disease without being affected by it. Once infection occurs, the disease may be spread from one person to another.

SOURCE